Exciting news for all Kids in the Hall fans: CBC is now offering all the episodes of Kids in the Hall — yup, that's right: all 5 seasons! You can check them out here.

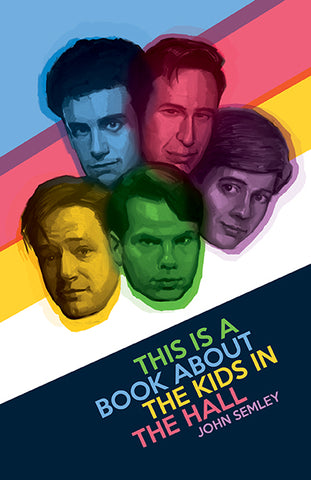

To celebrate, we're offering 25% off all preorders of our upcoming title, This Is a Book About the Kids in the Hall by John Semley, set to be released this October. Just use the discount code KITH25, active until July 15, 2016. Here's a sneak peek inside the book:

1 / archaic hertitage

The shared dream of the “beautiful day you beat up your dad”

If you fought your dad, how would you do it?

Don’t pretend like you’ve never seen your old man laid out on the chesterfield after 11 p.m., face bathed in the putrid neon light of a local news broadcast blaring on a too-loud television and imagined just—BLAMMO!—socking him in the face. Then he wakes up and pulls his sweat-misted T-shirt over his head like a hockey goon jerseying another hockey goon and—BIF! BLAM! ZIP! ZORK! KAPOW!—you throw a flurry of jabs into his compromised, middle-aged dad-gut. And then, as he’s curled on the ground, out of breath like he’s been run over by a twenty-tonne truck made out of pure, industrially wrought, nail-hard SON, you take a sip of the premium domestic beer he had sitting coasterless and half empty on the coffee table, wink at him, and goad, “Who’s the dad now?!”

Is that how you’d do it? It’s a question at the heart of one the quintessential Kids in the Hall sketches. It opens with Mark McKinney reading a newspaper. The headline reads, PARENTS DISAPPOINTED WITH THEIR KID, over a photo of a dopey child. The troupe is gathered around a table, performing in character as versions of themselves, preparing white bread sandwiches and talking about Shelley Long, when Scott Thompson asks the question, “Hey, any of you guys ever beat up your dad?”

They’re all taken aback at first. Beat up your own dad? Lord, no. But . . . sure. Maybe they’ve thought about it. I mean, who hasn’t? Before long, they’re laying out their own intricate fantasies of paternal pummelling. McKinney would take on his dad drunk, at a wedding. McCulloch would hide in a tree, and get the literal drop on his dad on the way to work, then club him with his own lawn. Foley would get his while he was watching TV. “I’d wait till he’s in the den, watching ALF, eating off a TV tray, wearing those slippers,” he says. “Then I’d blind him with salt, bash him on the head with the channel changer, and—and then I’d take down that big marlin over the bar. You know that stuffed marlin I’ve been staring at all my life? I’d take that baby down and, well, no more ALF today, daddy!”

McDonald, well, he says he’d let his dad beat him up—then let the guilt eat away at him. “Passive-aggressive,” McKinney chimes in. “That counts!” As for Thompson himself? Well, he couldn’t do it. He loves his dad. The rest of the troupe chirps up. Sure, sure, they all love their dads. But have they ever told their dads they love them?

“If you had the guts,” Thompson follows, “how would you do it?”

McKinney pipes up first. “Drunk. At a wedding . . .” And so the cycle begins again.

---

Issues with dads, stepdads, and de facto father figures constitute a major theme of The Kids in the Hall. There are countless sketches on the subject. Beyond the one recounted above, there’s one in which a churlish father (McCulloch) takes his son into the woods on the occasion of his thirteenth birthday, so he can watch his dad get “dead drunk.” “Take off that party hat,” McCulloch warns him in the car. “You won’t need it where we’re going.” There’s also McCulloch’s loathsome mutant Lothario, Cabbage Head—who is just what he sounds like: a man with a cabbage for a head—who consistently attempts to excuse his shabby, sexist behaviour by shrugging and offering, in a shrill sing-song apology, “I haaaaaaad a baaaaaad chiiiiiiildhoooood.”

There’s a “Police Department” sketch in which McCulloch talks about never telling his dad he loves him (because he doesn’t love him). There’s “Weekend with Daddy,” in which McDonald plays a borderline catatonic barely taking care of his two children following a devastating divorce. There’s the tenuous fighting between scrappy rebel teenager Bobby Terrance (McCulloch) and his stern father (McKinney). There’s “Daddy Drank,” a sorta- autobiographical piece in which McDonald recounts his father’s (played here by Foley) misadventures in alcoholism and how they tortured McDonald through his youth. There are all kinds of deadbeat dads and philandering husbands and, generally speaking, very little in the way of positive male role models.

It’s a theme that the Kids (McCulloch and McDonald in particular) have further pursued in their solo careers. A second-season episode of McCulloch’s sitcom Young Drunk Punk sees title teenager Ian (Tim Carlson) repeatedly antagonized by his hard-nosed father (McCulloch), who’s begging for a fight. (Instead, Ian merely stares meaningfully into his dad’s eyes, intimacy and emotion proving, as ever, the ultimate weapon against fatherly obstinacy.) The episode seems indebted to discussions, which McCulloch brings up in his book, between friends regarding “the beautiful day when you beat up your dad.” “Growing up,” he writes, “taking on your own man is practically a rite of passage.”

In 2008, McDonald premiered his one-man show Hammy and the Kids at Montreal’s Just For Laughs comedy festival. The show saw McDonald working through issues with his two dysfunctional families: his biological one, and specifically his alcoholic father, Hamilton “Hammy” McDonald, and the Kids in the Hall themselves. Promotional material for Hammy and the Kids tried to sell the sad, macabre, semi-therapeutic show with lines like “Drunk dads are hilarious!”

Whether or not drunk dads are actually hilarious—like out there, in life, in the real world—is one thing. My suspicion is that they’re probably not. But what matters is that something as tragic and traumatizing as a drunk dad can be made funny. The anguish, confusion, and anger of growing up under the thumb of an alcoholic father is spun into comic gold by some remarkable, Rumpelstiltskinian sorcery. This is what so much of comedy is, and especially what so much of the Kids in the Hall’s comedy is: gathering up the slings and arrows of misfortune that life volleys at you, and slinging them right back. Comedy is about turning the pain and banality of existence against itself. Comedy is about beating up your drunk dad.

---

Kevin McDonald isn't shy about it. His dad was a drunk. And the rest of the Kids in the Hall—with the ostensible exception of Mark McKinney—all had dads who were abusive in one way or another. “The four of us had drunk dads, or abusive dads,” McDonald tells me. “And we were from the suburbs. I don’t know if it’s the same thing now, but in the ’70s the suburbs really defined you. Living in the city really defined you too, but we were all from the suburbs, even though they were different suburbs. It adds to the chemistry, somehow, that we’re all from the same place and we all had abusive dads.”

Kevin McDonald was born on May 16, 1961, in Montreal, Quebec, the son of Sheila and Hamilton McDonald. His father sold dental supply equipment. His mother worked at home. When Kevin was a child, the McDonalds (including younger sister Sandra) were uprooted from Montreal to Los Angeles, and then back to Canada, landing in Toronto. McDonald was a chubby, asthmatic kid who spent much of his time indoors, watching television. He loved comedy. Steve Martin and Richard Pryor were his favourites.

One day in grade five, his science class was learning about the pith-ball electroscope, an early scientific instrument that detects the presence and magnitude of electric charges. His teacher asked if McDonald knew where pith balls came from. McDonald responded, “I don’t know, Pith-burg?” It was the first time he remembers making other people laugh. Later, while serving as an altar boy in his Catholic church, he slipped and fell, bringing a ceremonial crucifix down with him. The parish priest chided him for cracking up the congregation.

Once, while he was in his childhood bedroom, McDonald’s alcoholic dad burst in to berate his young son for no reason. “How many girls called you today, Kevin?” the elder McDonald asked. “Zero? How many called you the other day? Zero? You know what zero times zero equals, don’t you? Zero!” The incident typified McDonald’s youth. It was later the basis for the “Daddy Drank” sketch on The Kids in the Hall—albeit with the punchline juiced up a bit, revising the belittling arithmetic to add further insult to injury. In the sketch, Foley (playing McDonald’s dad) adds, “Well, you know what they say, son: zero plus zero equals fag! Zero times any other number always equals FAG! Think about it, ya little mathematician.”

Deep in another Toronto suburb lived another would-be Kid in the Hall, raised on TV comedy and emboldened by his own wisecracking. David Foley, born January 4, 1963, was raised in Etobicoke. Then its own municipality, known for its ethnic diversity and suburban sprawl, Etobicoke was dissolved in 1998 when the City of Toronto amalgamated its outlying suburbs into the “Megacity.” For a particularly dark period in the early 2010s, Etobicoke was the heart of “Ford Nation”—the hyperconservative base of bumbling, drug-smoking, controversial Toronto Mayor Rob Ford and his bullying brother, city councillor Doug Ford, both proud sons of Etobicoke.

Foley—the son of Mary, a homemaker, and Michael, a pipe-fitter—was raised on reruns of The Dick Van Dyke Show, his head filled with idle fantasies of his own future in show business. The young Foley’s interest in comedy was nurtured by his parents, who exposed him to the major concerns in both American and British comedy. “I grew up with everything that was good on the BBC in Canada,” Foley says. “My parents used to keep us up late to watch Python. I didn’t understand it, but it was cool. There were boobies in it!”

Foley was terminally shy as a boy. He read the dictionary for fun. According to Mary Foley, he was known to run away whenever someone produced a camera.4 Foley and his parents figured that instead of taking his bow before the camera, he’d end up as a writer—less Dick Van Dyke, more Carl Reiner. He remembers his classmates lighting up when he’d read his funny stories in class. In his youth, Foley harboured ambitions of writing comic novels. “I realized how hard it was,” Foley told me. “I mean, I have to write as part of what I do. But it’s a terrible job. Writing? It’s just an awful thing to do. Hard, hard work. Not fun, in any way at all.”

Foley was a little bit dyslexic. And a lousy student, known for his chronic truancy. High school did nothing for him. Neither did the alternative school he enrolled in in Toronto. So, at age 18, Dave Foley dropped out to pursue a different kind of education. First, he took an improvisational comedy class at the Skills Exchange, an adult education co-operative that operated in Toronto from 1977 to 1986. Then, at the prodding of his teacher, he enrolled in a Second City comedy workshop.

“My dad was a boozer and a salesman,” writes Bruce McCulloch in his 2014 memoir Let’s Start a Riot: How a Young Drunk Punk Became a Hollywood Dad. The book is loaded with stories about Ian McCulloch’s drunken, deadbeat parenting. “For me,” McCulloch told the Globe and Mail around the time of his book’s publication, “the traditional dad is a guy who drinks rye and ginger and watches the TV and screams at it.”5

From age eight onwards, Bruce McCulloch and his older sister played a game called “Find Daddy’s Car”: where on the streets of Edmonton had their father ditched the family auto during a long night of drinking and carousing? In 1971, when he was ten, little Brucio was tasked with driving his dad—“lit like a firecracker” following a Grey Cup[1] party—home in the family’s old Chrysler Cordoba. One summer, at the family cottage, McCulloch Sr. lost his false teeth in the lake, after executing a cannonball, and offered five bucks to whichever neighbourhood kid could successfully fish his dentures out of the cold water.

And, yes, one cold wintry day in Edmonton, Bruce McCulloch claims, he tried to clean his old man’s clock. A twelve-year-old McCulloch swung a bag of garbage at his shirtless pop. But he missed, falling into a snowbank. Soon after, in the autumn of his thirteenth year, McCulloch made another attempt to wallop “ol’ Ian” (as Bruce refers to his father with mock affection in his memoir), planning to knock him out with a TV tray. Instead, they ended up bonding over the Who bassist John Entwistle’s playing on the record Quadrophenia. “By the time I was old enough and strong enough to trounce him,” McCulloch writes, “I didn’t want to anymore. I was busy. Anyway, as it turned out, life ended up doing it for me.”

As depicted in Let’s Start a Riot, Ian McCulloch is almost a parody of mid-twentieth-century fatherhood, when dads only spoke to their kids to offer world-weary advice. When a dad would never dream of telling his kids he loved them, even if he did. McCulloch’s dad is also, unsurprisingly, the apparent prototype for most configurations of fatherhood that crop up again and again in the Kids in the Hall’s comedy. When he died, only a handful of people showed up to the funeral. “There were six people there, including him,” McCulloch told me. “Because he was such a prick.”

McCulloch’s mother worked at the local Woolco, that old chain of U.S.-owned discount retail stores that was ubiquitous in Canada throughout the ’70s, ’80s, and early ’90s. (Woolco went under in 1982, closing over 300 U.S. stores, but it operated for more than a decade thereafter in Canada.) McCulloch describes himself as a “rock music obsessed” kid. He gorged on glam rock records and made strange sartorial decisions—like wearing nurse’s pants to school, or several neckties at once. (Adolescence may not have particularly been easy on McCulloch, but he also made very few earnest attempts to make it easy on himself.) The cowboys would hurl homophobic epithets at him, and administer beatings. Yet they couldn’t seem to beat the weirdo out of him. Despite his self-styled dorkiness, he was something of a natural athlete. He competed in track-and-field and swimming, winning some provincial titles.

After high school, McCulloch moved to Calgary to attend Mount Royal College. He studied business. But, like Foley, he had no real knack for academics. (Or, maybe, no genuine interest.) He pulled in middling grades and switched his major to journalism, where he discovered his talent for writing.

Mark McKinney also lived in Calgary in the early 1980s. Before that, he had no real fixed address. Born in Ottawa on June 26, 1959, McKinney spent his youth shuttled all over the globe. His father, Russell McKinney, was a Canadian diplomat. His work took the McKinneys all over. Mark, his father, his mother, Chloe (an architectural writer), and siblings Nick and Jayne, resided in Trinidad, Washington, D.C., Mexico, and Paris. Thus McKinney was never settled, constantly adapting, always trying to fit in.

Years later, he’d call the experience of moving around so much “dislocating.” This sense of placelessness would benefit him later in his comedy: ever the chameleon, McKinney can fit into characters (and do foreign accents) with Peter Sellers–like aplomb. Sellers was an early comic idol of McKinney’s, along with more refined actors like Rod Steiger and Daniel Day-Lewis—performers who could totally immerse themselves in roles, disappearing altogether. While the other Kids in the Hall suffered childhoods of depression, abuse, or neglect, McKinney’s youth was considerably more privileged. “Mark’s a different one,” Kevin McDonald tells me. “But spiritually, he’s the same as us . . . Mark’s dad wasn’t abusive. But he was distant.”

“Mark had a more rarefied life than we did,” Scott Thompson agrees. “We all felt like outsiders. You don’t have to be a gay kid to be bullied. Lots of straight kids can be bullied as fags. Mark’s like his own creature. Mark’s dislocation, I think, comes from being raised all over the world. It was a different kind of abuse, in a way. Neglect, maybe. Having to always fit in and having to recreate yourself in different places. Maybe that’s what gave him his talent, allowed him to become anybody.”

McKinney eventually settled in St. John’s, Newfoundland, in 1980. He went to study political science at Memorial College—one of Canada’s top universities, and the largest in the Atlantic provinces. But wouldn’t you know it? He too was a bad student. (Years later, he’d be diagnosed with attention deficit disorder, which accounts for his inability to focus on schoolwork.) He eventually flunked out of university, but not before logging some hours at the campus radio station. It was there that he got his first taste of making people laugh, performing what he calls “funny voices for commercials.”

Scott Thompson was another chameleon, always looking for a place to fit in, or a place to hide. Born John Scott Thompson—maybe the WASPiest name in a sketch troupe that also includes a McCulloch, a McDonald, and a McKinney—on June 12, 1959, in North Bay, Ontario, he was one of five boys. Large families like that tend to instill sociability pretty quickly. You either learn to get along with the rest of the family or, well . . . you don’t have much choice in the matter, really.

As a kid, Thompson made friends easily and bounded between different social circles. “I was very social and I got along with everyone,” he told interviewer Jesse Thorn in 2011. “I think that might be a very classic trait of gay kids, particularly back then; now, maybe not so much. They’re more accepted, they don’t have to develop those kinds of skills the same way that we did.” Those social skills benefited him when his family moved from North Bay to the Toronto suburb of Brampton—also the home of notable Canadian funny guys Russell Peters and Michael Cera.

Thompson attended Brampton Secondary School, where, at 11:35 on the morning of Wednesday, May 28, 1975, sixteen-year-old student Michael Slobodian arrived with two guns squirrelled inside a guitar case. Slobodian opened fire in a boys’ washroom with a .22-calibre semi-automatic rifle and .444-calibre lever-action rifle, murdering student John Slinger. He also shot and killed Margaret Wright, an English teacher, and wounded thirteen students in her classroom. Then, Slobodian shot and killed himself—suicide being the coward’s fate that tends to cut down school shooters like this.

During the rampage, a teacher pulled Thompson into a classroom, where cooped-up students made panicky plans to assault any would-be attackers with their protractors, while others tried (and failed) to break open the classroom -windows with their chairs. Thompson and his fellow students were eventually escorted out of the classroom, marching single file out of Brampton Secondary. On their way down the hall, police instructed them to “look left,” lest they risk being traumatized by the mutilated body of their classmate, lying on the hallway floor. “Everything is so sharp and vibrating,” Thompson recalled in 2015, on the fortieth anniversary of the attack. “You’re alive in a way that you’re not normally.”

The school was reopened after the weekend. When he returned to school on Monday, Thompson remembers, there were still bloodstains in the boys’ room, a harrowing, unscrubbable reminder of the first mass school shooting in Canadian history, and one that still haunts Thompson decades later. In April 1999, on the night of the Columbine High School massacre in Colorado, Thompson says he was visited in a dream by the ghost of his late English teacher, Margaret Wright. She ordered him to turn the pain into art. “I want you to dance with my bones,” the apparition told him. To this day, the sound of popping balloons still triggers Thompson’s anxiety, the sound too close to the bursts of Slobodian’s rifle.

In high school, imagining a way out of such doldrums and very real, close-to-the-bone violence, Thompson dreamed of being a dancer. But he knew his parents wouldn’t buy it. After high school, he was accepted at Ottawa’s Carleton University to study journalism. Instead, he stayed closer to home, heading to Toronto’s York University. He told his parents he was going to study journalism. Instead he began work on a theatre degree. Eventually, he had to come clean. “I told them I was going to theatre school and they hit the roof,” he remembers. “I might as well have said that I was sleeping with a big black man—that came later.”

In his third year at York, he was asked to leave the university due to his “disruptive” behaviour. Onstage, he was an explosive performer. He was learning to be himself, and to express his sexuality. By his own account, his improvisational exercises and scene studies would turn combative, even violent. He’d often end scenes by trying to fight other students. He was unruly in classrooms. He talked back to his teachers.

Around this time, he took off to Alberta for a spell, to study musical theatre at the Banff School of Fine Arts (now known as the Banff Centre). It was there that Thompson took his first steps toward comedy, in a stand-up showcase. His comic debut was, in his estimation, “a disaster.” As a younger man, he had no real interest in comedy. Or, at least, no interest in being a comedian. “I didn’t realize that it was possible that I could be a comedian,” he has said. “I didn’t understand that that was an option. I thought comedians talk about their life; I can’t talk about my life, therefore, I must be an actor and act other people’s lives.”

It would be a few years before Thompson realized his true comic potential. He’d yet to find the troupe that would bring out the best—and, sometimes, the worst—in him. But he had faith. And a loose belief in numerology. “Five was a magic number,” he tells me. “I come from a family of five boys. Five’s the number in a hockey lineup. That was it.”

---

Five. Yes. Five guys. Five different backgrounds. Five different sets of experience and five different comic sensibilities.

Yet across the expanses separating them, from suburb to suburb, across provinces and political lines, there was a shared feeling about the world. It goes back to that word McKinney uses: displacement. Once, while I was interviewing Bruce McCulloch, he told a great story that illustrated this idea of a sensibility, one shaped in part by a kind of cockeyed empathy with the world around him.

I was walking down the street and saw this sign. Someone had lost a teapot and posted “Lost Teapot” and then a reward. I took a picture of it. Fuck, it drove me crazy. It was so funny, that someone would lose a teapot and put up a reward for that teapot. That weird thing about humanity just drives me crazy.

What’s just a stupid teapot to you or me or Bruce McCulloch, or any other person passing by this “Lost Teapot” sign, clearly means something to someone. They were knocked off-centre by the disappearance of this common household item, so much so that they’d bothered posting a reward for a lost teapot instead of just, you know, using the allocated reward money to go to the store and purchase a replacement. There’s an abounding empathy there—and a profound ridiculousness. The ad could have just been a joke, calculated to drive people like you or me or Bruce McCulloch crazy. It could have just existed to make us laugh. These small, weird anomalies that we come across in life may be microcosmic, or they may signal nothing beyond their own unique weirdness. The world is full of bizarre and beautiful little filigrees like this: things that mean everything to someone and pretty much nothing at all to most everyone else. This smallness, this particularity, is beautiful and wonderful in itself. Sometimes.

It seems to me that great comedians possess their own way of viewing the world. They share a gift for taking the often overwhelming overstuffedness of everyday life and shaping it into something recognizable and funny. Theodor Reik, a psychoanalyst and student of Sigmund Freud, noted in his book Jewish Wit that humour serves as a mechanism for transcending adversity, permitting ownership over something awful. Through humour, Reik wrote, “lament often turns into laughter.” Whistling past the grave. Laughing through tears. Gallows humour. All that stuff. Mark Twain put it even more generally: “There is no humour in heaven.” Without scorn, pathos, and sadness, there would be no reason to laugh. Existence is cruel and absurd. As the Kids in the Hall succinctly put it in the opening scene of their feature film, Brain Candy, “Life is short, life is shit, and soon it will be over.”

It’s something of a cliché that all comedians come from a place of disprivilege. Yes, you can certainly analyze how humour functions in marginalized populations, like Jewish communities or black communities. But is it necessarily a hard-and-fast rule that all good comedy bubbles up from a sense of oppression? Kevin McDonald, for one, doesn’t think so. “Someone like Robin Williams or Steve Martin probably wasn’t marginalized,” he points out. “I don’t think you need to be marginalized to be a funny person. But when you are a funny person, and you are marginalized, that’s something that drives you there. It’s just not the only thing that drives you to be a comedian. But it’s an obvious, concrete thing that drives someone whose natural bent toward comedy would lead there anyway. I think there’s a lot of people who don’t feel marginalized. I think you’re funny if you’re funny.”

Plenty of people have pondered that whole “sad clown” idea. The notion that you can’t be funny if you’re happy has also become a rote way of writing about, or even considering, comedy and comedians. Some of the highest-profile comedians have rejected the idea outright. “There are a lot of unhappy people driving bread trucks,” Jerry Seinfeld once said. “But when it’s a comedian, people find it very poignant.” It’s hard to make the case that five white middle-class Canadian guys were marginalized. (Well, except maybe for Scott Thompson, the only one of the crew that’s not a straight white middle-class Canadian guy.) But tucked away in the sleepy suburbs of a sprawling—and, let’s face it, usually pretty boring—nation, something churned inside these five guys.

You may not have to be unhappy, or marginalized, or ill-at-ease in your skin to be funny. But for the Kids in the Hall, it sure didn’t hurt anything. There was a sense of alienation. Or of just being different. Being funny, whether by wearing ironic pyjamas or doing goofy voices on a college radio station or exploring improv, was a way of fitting into the world. Or maybe just a way of snickering at it, of turning lament into laughter. There was always that lingering sense that there was something else—beyond the unforgiving high-school classrooms and the household hallways haunted by the lumbering presence of dads drunk on rye and ginger. They were all standing just outside, or just to the left of, the rest of the world.

Maybe this explains their consistent, shared fascination with failed fathers and bad dads. I mean, it’s Freud 101 stuff. Yes, there’s the Oedipus complex: that mythic belief that children come first to identify with their opposite-sex parent, leading to a basic desire in boys to kill the father and sleep with the mother. And yes, that that deep-set Oedipal tension, especially when left unresolved, can play itself out in all kinds of ways: from a healthy suspicion of police and teachers and others who hold the authoritarian sway of the father, to dating women who look suspiciously like the mother.

But there’s another idea from Freud I want to point to here, which goes beyond Oedipus’s particular sexual proclivities and beyond conceptions of humour. It’s the idea of archaic heritage. Basically, systems of the primitive world linger in a kind of collective unconsciousness, the past glomming onto the present like an unshakeable residue. “All that has once lived clings tenaciously to life,” Freud wrote in the 1937 paper “Analysis Terminable and Interminable.” In this sense, he borrows a bit from Darwin: where certain genetic traits are passed from generation to generation, so too are certain deep-seated kernels of psychological reasoning (or unreasoning).

For Dr. Freud, early cultural formations take root somewhere deep inside of us. Chief among these is the notion of the primal horde—a primitive social formation “ruled over despotically by a powerful male.” In Freud’s primal horde, the so-called primal father rules over all the women, and he has to be destroyed in order that a “community of brothers” may reign. Freud acknowledges that this is merely a theory, a “just-so story” imagined in part to establish a certain sense of psychological coherence, of understanding the ways individuals function within larger group dynamics. Still, the lesson is clear.

In Freud, as in The Kids in the Hall, as in life, the father is the first enemy. The dad is the primal source of suffering, anguish, and anxiety. And, I’d say, your father doesn’t need to be drunk or to hoard all the women to enact this role. The father merely has to exert that early authoritarian sway. The father has to put across the idea that the world is defined by his power, proscribed by whatever nominal authority he may possess. The father is that original domineering force that must be overpowered in order for the child to assert their own identity and individuality. The father has to introduce that notion of defining yourself not in accordance with something—a culture, a religion, a set of values, a guy who stalks around your childhood home and pays the gas bill and sleeps in the same bed as your mom—but in antagonism to something. The father has to be the original enemy. The father just has to be a father.

It’s such a nice image, in its way. Imagine those five guys—Kevin, Dave, Bruce, Mark, and Scott—tucked away in their childhood beds across Canada (or, in McKinney’s case, in one or another foreign port) fantasizing about that day when they’d somehow build a world they’d fit into, dreaming of “that beautiful day when you beat up your dad.” Maybe this is why the Kids in the Hall were fixated on fighting their fathers. And maybe it’s why they made an entire career of pushing back against expectation, bucking authority, making their own mistakes, and searching, in noble desperation, for the next drunk daddy to beat up.